Women

in Love

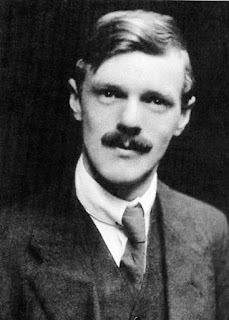

When I was in high school, I cannot remember what year

exactly, one of my Christmas gifts that year was an omnibus edition of D.H.

Lawrence novels. I may have heard of Lawrence before that voluminous book came

my way, but once I read the novels contained in that edition, I wanted to read

more of him, and about him.

When I was in high school, I cannot remember what year

exactly, one of my Christmas gifts that year was an omnibus edition of D.H.

Lawrence novels. I may have heard of Lawrence before that voluminous book came

my way, but once I read the novels contained in that edition, I wanted to read

more of him, and about him.

When we read Lawrence now, some of us may marvel at the skill

of his writing, at how much psychology is at work in all of his novels, or how

he writes of the human condition. Back when he was writing, however, Lawrence

could not get published for the things he wrote about. His works were

controversial for the candid way in which he treated sex. He often had to do

revisions and some publishers refused to publish his work. Today when we read

his work, we may wonder what all the hoopla was about, but mores were different

in the England post-World War I. As recently as the 1980s, Lady Chatterley’s Lover was banned in China for fear of “corrupting

the minds of young people”, and “going against the Chinese tradition.” In the

1960’s, a group called Mothers United for Decency, got a trailer, turned it

into a “smutmobile” and displayed books considered objectionable, including Sons and Lovers. This novel closely

examines working-class conditions in a mining town, as well as relationships.

It also has significance vis-à-vis psychology in that it depicts the Freudian

oedipal complex. What was once considered smut, is now considered one of the

finest books of the 20th century.

When we read Lawrence now, some of us may marvel at the skill

of his writing, at how much psychology is at work in all of his novels, or how

he writes of the human condition. Back when he was writing, however, Lawrence

could not get published for the things he wrote about. His works were

controversial for the candid way in which he treated sex. He often had to do

revisions and some publishers refused to publish his work. Today when we read

his work, we may wonder what all the hoopla was about, but mores were different

in the England post-World War I. As recently as the 1980s, Lady Chatterley’s Lover was banned in China for fear of “corrupting

the minds of young people”, and “going against the Chinese tradition.” In the

1960’s, a group called Mothers United for Decency, got a trailer, turned it

into a “smutmobile” and displayed books considered objectionable, including Sons and Lovers. This novel closely

examines working-class conditions in a mining town, as well as relationships.

It also has significance vis-à-vis psychology in that it depicts the Freudian

oedipal complex. What was once considered smut, is now considered one of the

finest books of the 20th century.

My favorite novel by D.H. Lawrence remains Women in Love. It is a sequel to The Rainbow, but it can be read apart

from that. It is the story of two sisters, Ursula and Gudrun Brangwen, and

their relationships with Rupert Birkin and Gerald Crich, respectively. This

novel was published two years after the end of World War I. Reading it, we see

a world in

crisis, or humans in

crisis, through the conversations of certain characters, such as Ursula and

Birkin. We see Lawrence digging deeper in search of a more vital life, a life

fully lived in every way. Not as he felt many people were living in his day. In

the passage below, Birkin expresses his feeling for humanity at present:

Birkin looked at the land, at the

evening, and was thinking: “Well if mankind is

destroyed, if our race is destroyed

like Sodom, and there is this beautiful evening

with the luminous land and trees, I

am satisfied. That which informs it all is there,

and can never be lost. After all,

what is mankind but just one expression of the

incomprehensible. And if mankind

passes away, it will only mean that this particular

expression is completed and done.

That which is expressed, and that which is to be

expressed, cannot be diminished. There

it is, in the shining evening. Let mankind

pass away—time it did. The creative

utterances will not cease, they will only be

there. Humanity doesn’t embody the

utterance of the incomprehensible any more.

Humanity is a dead letter. There

will be a new embodiment, in a new way. Let

humanity disappear as quick as

possible. (Lawrence 50-51)

What

Birkin is hoping for is a new humanity, with a new expression. Not the old,

tired ways of doing things. What precedes this thought process is Birkin’s

dissatisfaction with the way people live life now, calling it “dreary.” He

suggests breaking up society altogether to form something new, to change. How

he intends to do that is never quite certain. Whatever it may be, will be

different from the social order that exists.

It is

this digging in search of a deeper meaning or fulfilment of life that gives Women in Love its flavor. There is much more to Women in Love than women being in love. It is an exploration of the

possibilities of different kinds of love. It is a conversation on how to be

fully alive. If you like philosophical

discussions as well as psychological explorations, I recommend this book that

remains on the list of Banned and Challenged Classics.

Comments